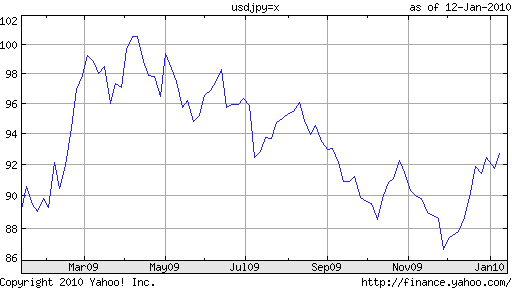

Last week, Hirohisa Fujii resigned as finance minister of Japan. Since Fujii was anoutspoken commentator on the Japanese Yen, the move sent a jolt through forexmarkets. Those who were expecting that his replacement, Deputy Prime Minister Naoto Kan, would be be more consistent than his predecessor were quickly disappointed, as Mr. Kan managed to contradict himself repeatedly within days of assuming his new post.

On January 6, he said it would be “nice” to see the Yen weaken, going so far as to designate 95 Yen/Dollar as the level he had in mind. One day later, he said that the markets should in fact determine the Yen: “If currency levels deviate sharply from the estimates, that could have various effects on the economy.” After he wasrebuked by Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama, who noted that the government should not talk to reporters about forex, he went on tell US Treasury Secretary that forexlevels should be stable. In short, Japan’s official governmental position on the Yen still remains muddled, and it’s no less clear whether it will – or even should – intervene.

Fortunately, they may not have to. Not only because the Yen still remains more than 5% off of the record highs of November, but also because economic and financial forces are coalescing that could send the Yen downward. Despite a recovery in exports, the Japanese economy remains beleaguered, having most recently contracted to the lowest level since 1991, as part of a “tumble [that] isunprecedented among the biggest economies.” Now that we are into 2010, it can be said officially that Japan has now suffered from the “second lost decade in a row.”

When economic growth collapsed in 1990, Japanese consumers became famously frugal, and the domestic market still hasn’t recovered. Neither has the stock market, for that matter: “The Nikkei is 44.3% below where it stood at the end of 1999. It is 72.9% below its peak near the end of 1989.” The performance of the bond market, meanwhile, has been a mirror image, rallying 78% since 1990.

The resulting decline in real interest rates has combined with economic stagnation to produce a perennial state of deflation. In fact, prices are once again falling, this time by an annualized pace of 2%.

As many economists have been quick to diagnose, the problem lies in a tremendous (perhaps the world’s largest) imbalance between savings and investment, as “Japan still has ¥1,500 trillion ($16.3 trillion) of savings.” It’s not clear how long this can last, however, as Japanese demographic changes tax the nation’s pool of savings. “More than a fifth of Japanese are over 65…The nation’s population began shrinking in 2006 from 127.8 million, and will drop by 3.2 percent in the coming decade.”

This brings me to the final component of Japan’s perfect economic storm: debt. Japan’s gross national debt is projected by the IMF to touch 225% of GDP this year, and 250% as early as 2014. As a result of the aging population, the pool of cash available for lending to the government is shrinking at the same rate as the tax base, which is exerting fiscal pressure on the government from both sides. According to one commentator, “Japan’s fiscal conditions are close to a melting point.” Another frets: “I doubt there is any yield that international capital markets can find acceptable that will not bankrupt the Japanese state.”

What is the government doing about all of this? Frankly, not too much. It is spending money like crazy – exacerbating its fiscal state and pushing it closer to insolvency – in a (vain) attempt to prime the economic pump and avoid deflation from further entrenching. The Central Bank, meanwhile, just announced a new round of quantitative easing, also aimed at fighting deflation. At only 2% of GDP, however, the measures are “pretty tame” and unlikely to accomplish much. Considering that its monetary base has only expanded by 5% this year (compared to 71% in the US), it still has plenty of scope to operate. At the present time, however, it is still reluctant to do so.

Ironically, the aging population phenomenon could end up restoring Japan’s economy to equilibrium. The worse Japan’s fiscal problems become, the sooner it will be forced to simply print money, so as to deflate its debt and avoid default. This will stimulate the economy and put upward pressure on prices (solving two problems), and exert strong downward pressure on the Yen. The way I see it, that’s four birds with one stone!

As for the Yen, then, I would expect it to hover over the near-term, since price stability and a strong credit rating don’t signal immediate catastrophe. No, Japan’s economic problems are more long-term, which means it could be a while before they more clearly manifst themselves.

No comments:

Post a Comment